Gimbal, Lock and imaginary solutions in the 4th dimension

William Rowan Hamilton first described quaternions in 1843 while crossing Broom Bridge in Cabra, Dublin, where he carved the formula into one of the rocks. There is a plaque commemorating the discovery on the bridge itself, it reads:

Here as he walked by

on the 16th of October 1843

Sir William Rowan Hamilton

in a flash of genius discovered

the fundamental formula for

quaternion multiplication

\(i^2 = j^2 = k^2 = ijk = -1\)

& cut it on a stone of this bridge.

When rotating a point in 3 dimensional space, it may not be obvious that to define the rotation 3 values, one for each axis for instance is not sufficient. All it takes is for one axis to become aligned with another relative to how they are rotating for there to be rotations that are no longer possible. 4 values are sufficient but how best you make use of them is just as important. An intuitive and effective, if suboptimal, approach is to use 3 of the values to define a vector for the axis of rotation with the 4th value being how rotated around the axis it is. This is understandable but can be both limited in its capabilities and can require a fair amount of work whenever it needs to be applied.

For a long time imaginary numbers, those numbers used when handling the square roots of negative numbers for instance, were fairly esoteric, stuck in the realm of the cubic equation and the like, so it is interesting how it has appeared in applied mathematics and even physics. The emergent utility appears to have come from how the imaginary numbers are effectively making use of another dimension in the number space, and as such multiplying by the square root of -1, a.k.a. i, has the effect of rotating the position in that space by 90 degrees.

Multiplying by an imaginary number such as this by a value produces a relative amount of rotation in that space and we can define and store that rotation by storing that value. A useful property of defining a rotation this way is that multiplying the values of 2 together produces their combined rotation.

In terms of composition; quaternions consist of 4 real numbers which are each able to be multiplied against an imaginary number. 3 of the values for the rotations of each of the dimensions which you can think of as being defined as the following:

\(x = v_{x}\sin(0.5\theta)\)

\(y = v_{y}\sin(0.5\theta)\)

\(z = v_{z}\sin(0.5\theta)\)

The forth value is is often called the scalar, but even this can be ambiguous, ~ and can be defined:

\[w = \cos(0.5\theta)\]Due to their efficiency and performance; quaternions have essentially become the standard method for handling rotations in 3 dimensional space, so even though their unintuitiveness may be offputting, it is worth maintaining some awareness. Many get away with using existing libraries without any further understanding, but, like with anything, the more you know about quaternions the better use you can get out of them.

I downright love how such elegance appears to emerge from an esoteric complexity.

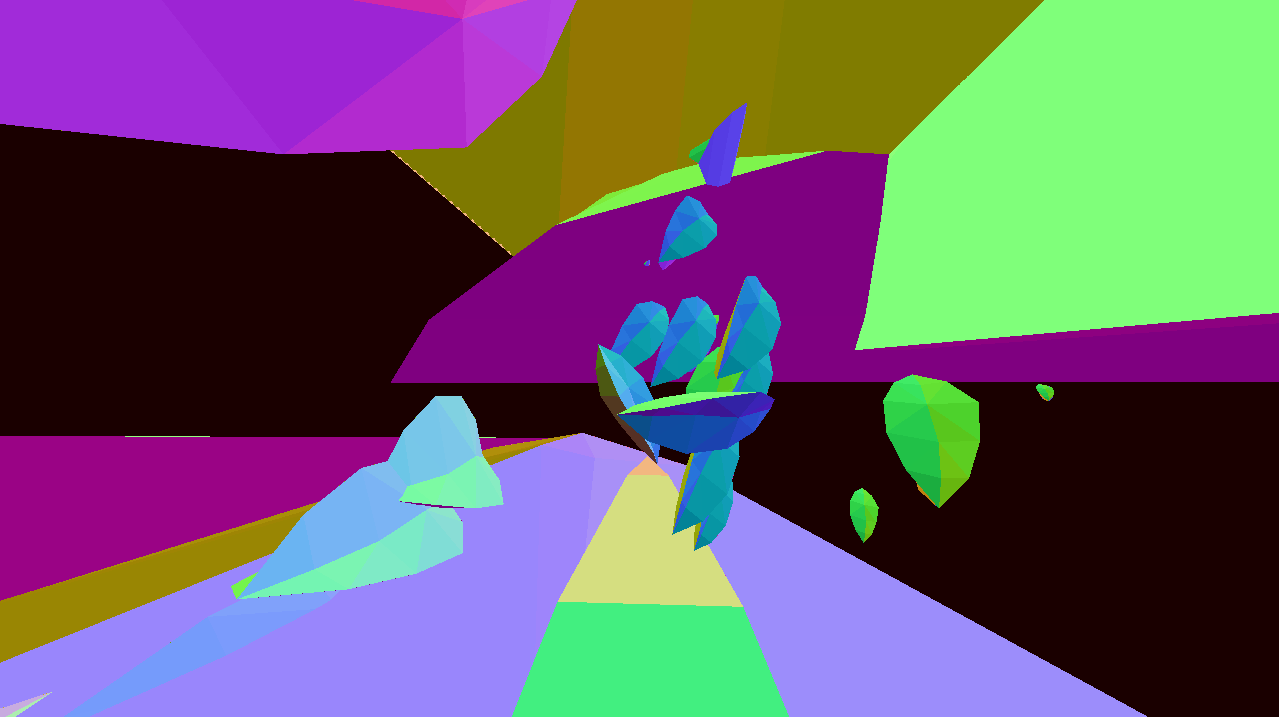

Above: an example of the dangers of quaternions.